Shamanism - An Ancient Tradition in a Modern World

Shamanism is believed to predate organized religions, with its roots tracing back to the Paleolithic era. Archaeological evidence, such as cave paintings and burial sites, suggests that early humans engaged in rituals to connect with the spirit world, seek guidance, and ensure communal well-being. Anthropologists often associate shamanism with animism—the belief that all entities, including animals, plants, rocks, and even celestial bodies, possess a spirit or consciousness. In such worldviews, shamans acted as intermediaries, facilitating communication with these spiritual forces for the benefit of their communities.

The term “shaman” entered the Western lexicon through Russian ethnographers in the 17th century. It derives from the Tungusic word “šaman,” used by the Evenki people of Siberia. Scholars suggest that “šaman” may be rooted in the Tungus-Manchu verb “sha-” meaning “to know,” thus emphasizing the shaman’s role as a “knower” or one who has profound spiritual insight.

Other hypotheses propose links to Sanskrit terms like “sramana,” referring to ascetics or seekers of spiritual truth, or even connections to proto-Indo-European roots. Regardless of its linguistic origins, the term has become a catch-all label for diverse spiritual practices worldwide, a generalization that sometimes obscures the nuances of individual traditions.

Traditional shamanism remains alive in many indigenous cultures, though it has adapted to the pressures of modernization, colonization, and globalization. Key regions where shamanic traditions persist include:

• Siberia and Central Asia:

Often considered the heartland of shamanism, Siberian shamans practice intricate rituals involving drumming, chanting, and trance states to interact with spirits. Despite Soviet-era suppression, Siberian shamanism has experienced a revival in recent decades.

• The Americas:

Among Native American and Mexican communities, shamanic practices often integrate ceremonies such as sweat lodges, vision quests, and the use of sacred plants like peyote or magic mushrooms. These traditions emphasize healing, guidance, and ecological harmony.

• Amazon Basin:

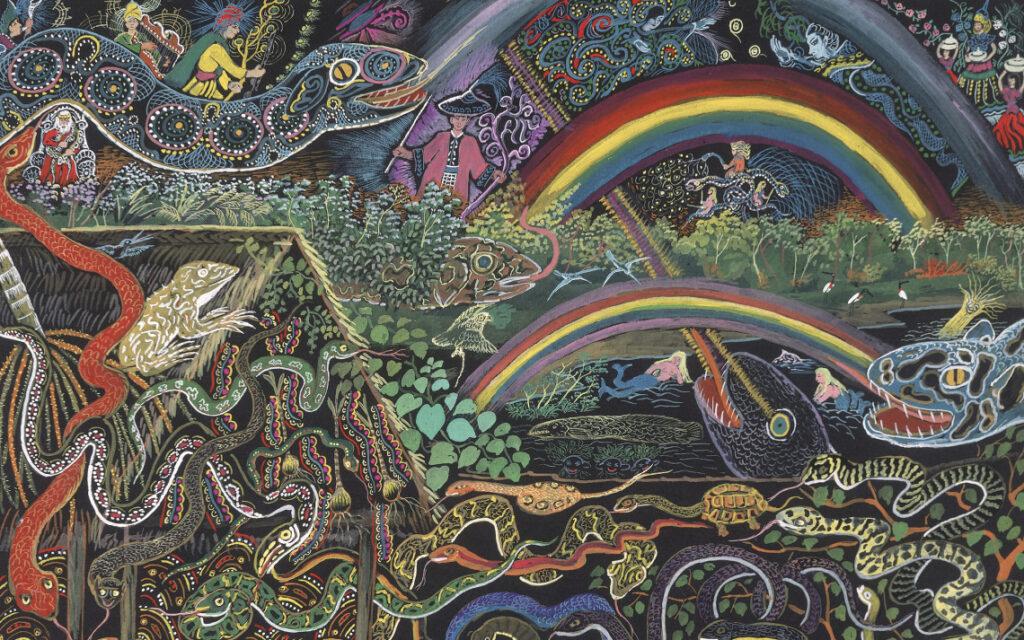

Indigenous groups like the Shipibo-Conibo, Yawanawa, Cofán, and Shuar, among others, are located in the Amazon region spanning Peru, Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador. They have maintained shamanic practices centered around ayahuasca. While their practices share many similarities, there are also clear differences in rituals and interpretations.

• Africa:

In sub-Saharan Africa, traditional healers often fulfill shamanic roles, using drumming, dance, and herbal medicine to connect with ancestral spirits and address physical and spiritual ailments. Bwiti, a spiritual tradition in Gabon practiced by groups like the Mitsogo, Apindji, and Fang, centers on the use of the psychoactive plant iboga for healing, initiation, and spiritual guidance.

• Australia and Oceania:

Aboriginal Australian shamans, or “clever men/women,” possess profound knowledge of the Dreamtime, the spiritual framework that informs their connection to the land and cosmos.

The Evolution of Shamanism

Shamanism has never been static. Throughout history, it has evolved and fused with other religious and cultural traditions. For example:

• Bön:

Bön is an ancient spiritual tradition from Tibet, predating the arrival of Buddhism in the region. It incorporates animistic beliefs, nature worship, and shamanic rituals, emphasizing a deep connection with the natural world and spirits. Over time, Bön merged with Buddhism, specifically Buddhist tantra, to form what is now recognized as Tibetan Buddhism.

• Mestizo Shamanism:

Mestizo shamanism originates from the blending of Indigenous, European, and African influences in Latin America, particularly in regions like the Amazon. The term mestizo comes from the Spanish word for “mixed” and historically refers to individuals of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry. This syncretic tradition incorporates native shamanic practices with elements of Christianity. It often involves the use of plants like ayahuasca for spiritual healing and guidance, combining Indigenous cosmologies with Western frameworks to address the needs of a mixed-cultural society.

• The Red Path (Camino Rojo):

The Red Path embodies a spiritual way of life rooted in the Indigenous traditions of the Americas, emphasizing harmony with nature, respect for ancestral wisdom, and a commitment to spiritual and communal balance. Central to this spiritual framework is the prophecy of the Condor and the Eagle, a profound vision that speaks to the unity of North and South American traditions. The term “Red Path” became more widely used in the 20th century, often associated with Pan-Indigenous spiritual revival movements. Elders and leaders from various tribes played key roles in revitalizing and sharing the teachings of the Red Path, making it accessible to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous followers.

Neo -Shamanism

The rise of global spiritual movements has brought shamanism to new audiences. Practices like ayahuasca ceremonies have become popular among Western spiritual seekers, often detached from their original cultural contexts. Iboga rituals have transformed into therapies for drug addiction, and magic mushrooms, once a sacrament to communicate with the divine, have become remedies for depression. The facilitators are often not initiated by elders of the original traditions. At best, they may have knowledge as psychotherapists, but in other cases, they may lack any experience, making the process often unpredictable.

Shamanism as a practice is not protected; indeed, there are so many different shamanic traditions that it is impossible to generalize or trademark it. It is crucial to distinguish between a lineage-based or traditional shamanism and the widely used term “shamanism” that can now be found anywhere. A growing trend called Neo-Shamanism mimics many traditional practices but lacks a connection to the tradition. These practices are borrowed and modified, often lacking authenticity and depth. Some are even offered in online workshops or virtual ceremonies, with social media shaping how shamanism is perceived and practiced today.

Given that there is no regulation, anyone can call themselves a shaman. This creates significant issues: on one hand, there are charlatans pretending to be shamans to feed their egos and make money; on the other hand, this undermines the credibility of genuine shamanic work. Imagine if anyone could call themselves a doctor and practice medicine without proper study, you would not trust in doctors and their profession anymore.

Cultural Appropriation

This has also led to significant controversy, particularly concerning cultural appropriation. Western practitioners often adopt shamanic symbols, rituals, and terminologies without fully understanding or respecting their cultural origins. This trend raises several ethical issues:

• Loss of Authenticity:

Stripping shamanic practices from their Indigenous contexts often distorts their meaning and purpose. Rituals may be commodified, reducing profound spiritual practices to commercialized wellness trends.

• Exploitation of Indigenous Communities:

The demand for shamanic experiences has sometimes resulted in the exploitation of Indigenous healers and sacred resources.

• Erosion of Cultural Identity:

When shamanic practices are appropriated without acknowledgment, it can undermine the cultural heritage and autonomy of the communities from which they originate.

Showing Respect

My personal experience learning from Indigenous people has always been positive. They were open to sharing their shamanic wisdom, even though some of their knowledge was reserved for their progeny or only shared with those who had spent significant time with them. Shamanism is a living tradition, and cultural boundaries should be respected. In most cases, Indigenous communities are happy that outsiders want to learn from them, considering that not long ago, they were discriminated against and called primitive for their lifestyle and practices. They want their traditions to continue to exist, but they must always be treated with respect.

For those drawn to shamanism, it is essential to approach it with humility and respect, recognizing it not as a monolithic tradition but as a diverse and dynamic tapestry of spiritual wisdom. Only by honoring its roots and the cultures that sustain it can shamanism remain a source of profound insight for generations to come. While it is not a rigid tradition and can be expanded upon, this should only happen when the foundations are preserved and respected.